This is the second in a series of three blog posts on the M4D space by Heather Thorne, Director of ICT Innovation at the Grameen Foundation’s Technology Center.

Grameen Foundation approaches all of its work from a “Theory of Change” perspective, using this as a starting point to ensure activities and outputs are logically linked to the desired outcomes of each program. AppLab’s Theory of Change is based on research showing that gaps in access to information and services (e.g., health, financial services, agriculture, markets, job opportunities, etc.) contribute to lack of economic opportunity and reduced welfare, therefore leading to or perpetuating poverty. This is worsened by inability to act on information. By leveraging mobile phones as a means to eliminate or reduce those gaps, and to reduce friction in systems, we believe it is possible to directly and indirectly reduce poverty.

Given the potential for M4D efforts to benefit a broad audience but possibly miss the specific needs of the poor, we do a number of things to ensure a focus on the poor and poorest in AppLab efforts, such as:

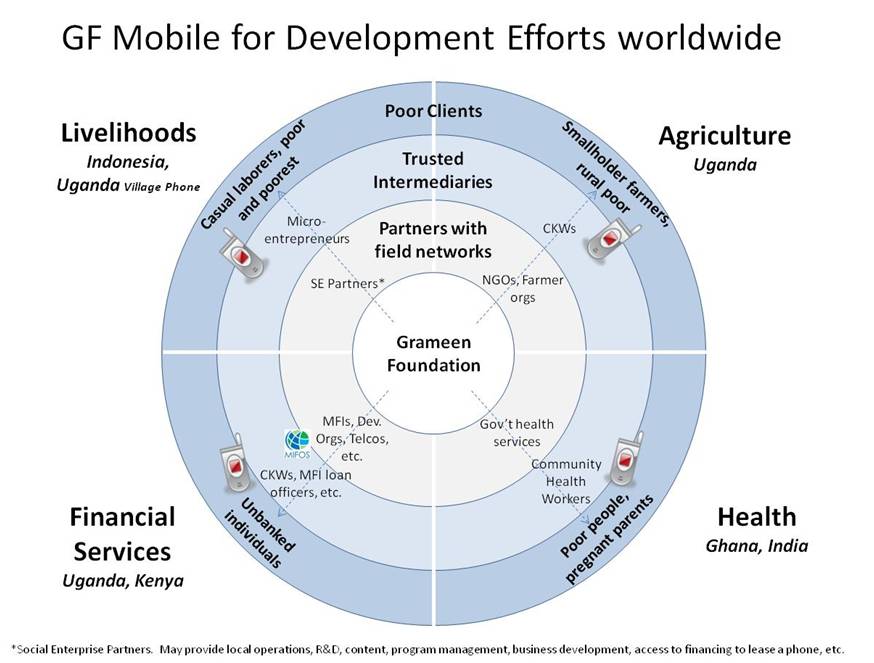

- selecting vertical areas known to have a statistical link to poverty (or lever for escaping it): agriculture, health, livelihoods, or access to targeted financial services

- incorporation of M&E frameworks and measurement approaches into each implementation

- geographical targeting focused on regions known to have larger populations of poor and very poor

- choosing mobile operators with the largest market share among poor populations we serve and choosing other NGO partners who share a poverty-focused mission

- pricing models, such as cross-subsidization, making services available to those unable to pay

AppLab’s Theory of Change has evolved over the 8 years we have been working in the M4D space, starting first with the Village Phone replication program in Uganda, which extended to Rwanda, Cameroon and several other sub-Saharan African countries, as well as to Indonesia. Building on this foundation, GF began exploring the potential for providing additional services through the phone nearly four years ago, leveraging the fact that low-end phones were beginning to penetrate even the most remote villages. We launched AppLab Uganda in 2007 in partnership with MTN Uganda and Google, and spent the next two years developing partnerships with local content providers in agriculture and health, conducting ethnographic research, rapid prototyping and concept testing, developing and testing products, and launching a nationwide suite of applications called Google SMS (GSMS) in 2009. In Indonesia, GF incubated an Indonesian-owned social enterprise called Ruma, which began to operate the Village Phone business in partnership with a large mobile operator focusing on the low-end market segment. The model began to evolve as we learned that voice services no longer presented a viable business opportunity due to mobile phone penetration—and the Ruma entrepreneurs began to sell airtime, a similarly low-cost item that people buy frequently, in small denominations, which can be delivered through the phone by people with minimal skill and working capital– increasing and smoothing their cash flow.

We recently completed what we believe to be the first ever randomized control trial designed to assess the impact of a mobile-phone based service aimed at improving the lives of the poor. The service we sought to measure was Google SMS (GSMS) Health Tips, and our social impact measurement partner, Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA), performed the study.

The learnings from the study were substantial, supporting some of our initial hypotheses and refuting others. They indicated that when people are made aware of such services, there is indeed demand and usage of them, and that ongoing awareness efforts in general are critical to usage and thus impact.

We also learned, however, that the fundamental drivers of behavior change are not altered simply because of the phone, and if the phone is not addressing each of those drivers, behavior change is unlikely. (You can read more about the study on Eric Cantor’s recent blog post) Driving sustained adoption of the information and behavior change, or other outcomes that we envision, requires re-thinking aspects of the service—one of which is the often necessary role of a trusted intermediary in creating awareness and reinforcing the desired adoption of information and behavior change.

You can read more about trusted intermediary’s and Grameen Foundation’s M4D work in Heather’s final blog post which will be posted later this week.